The Imposter Syndrome Cycle

In one recent call with a client, I distinctly remember them listing all of their certifications, degrees, and professional experience. It was incredibly impressive and clearly they would be a massive contribution to their new role leading a team in a large organization. However, that wasn’t what they felt. Not even close.

“I feel like I don’t even belong there. I feel so judged — by them, by myself. It’s paralyzing. I just can’t make a mistake. This imposter syndrome feels so suffocating.”

Imposter Syndrome has come up in almost half of my calls this month, which I hope lands as a balm for …all of us?

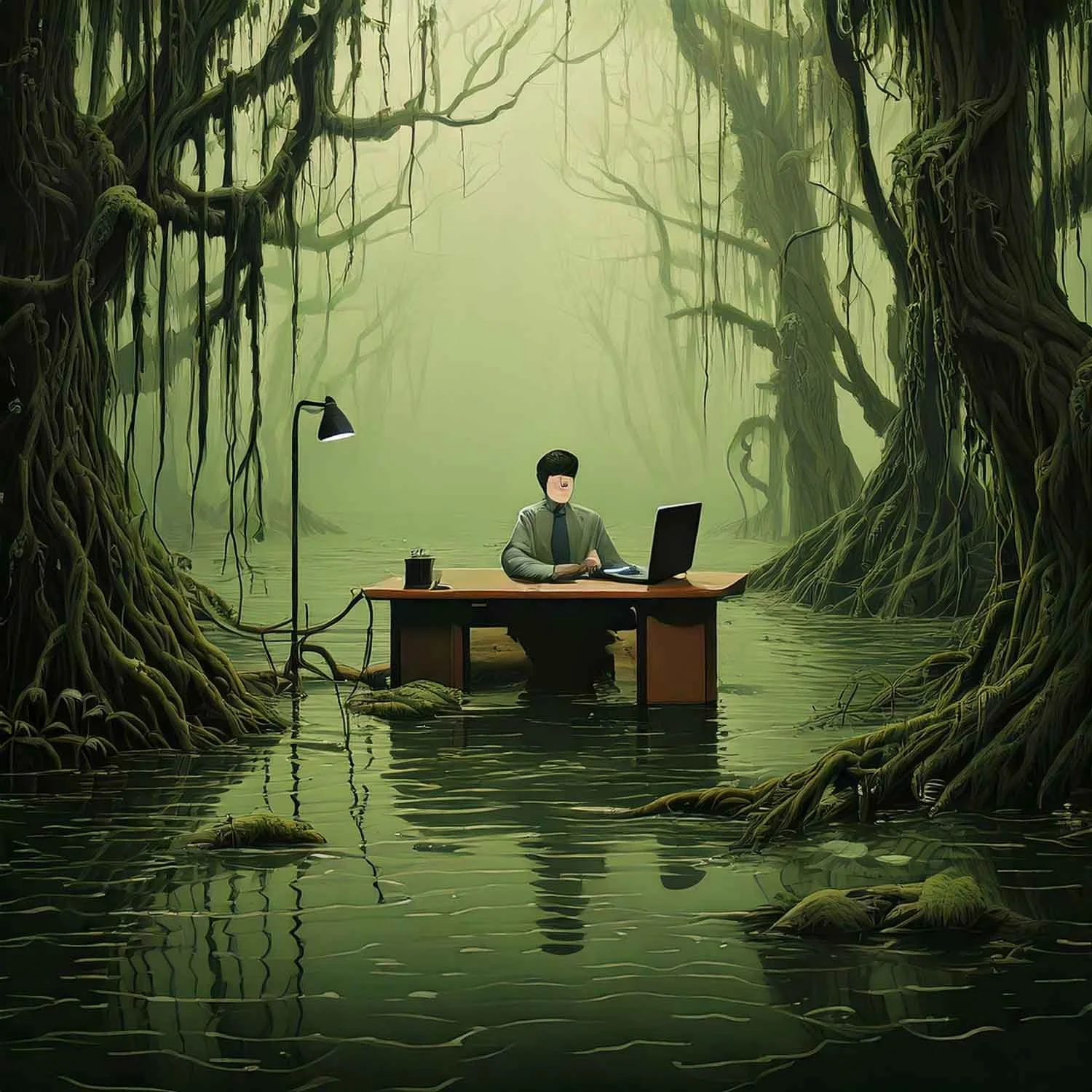

But what surprised me the most as I was reviewing my notes wasn’t the pervasiveness (it’s surprisingly common), but the shame my clients felt at experiencing it at all. They described something akin to twofer: the shame of not belonging, and then the shame of having shame of not belonging. It was a veritable swamp of shame.

According to a 2020 issue of the Journal of General Internal Medicine that includes a comprehensive review of 62 studies on Impostor Syndrome, up to 80% of us experience this, so you're in good company.

And, of course, I’ve had my own struggles with it. And by struggles, it felt more like a wrestling match.

In my past life before I was a business coach, I was an art director in the magazine industry, quite by mistake. Though I enjoyed a good issue of Bon Appetit as much as the next foodie home cook, it was never my plan to end up there, but through a series of fortunate/unfortunate events, there I was.

Like I suspect of many of us stumbling through our 20s, I was never someone who thought too much about my career in terms of thoughtful strategic trajectory. I tended to simply say yes to the next thing, which served me in some ways, but often left me feeling like I snuck in through the back door and didn't quite belong.

The messages my self-doubt sent me sounded like, "You'll never be able to design half as well," "Yeesh, I don't belong here," or "I hope they don't give me a huge project or I'll be found out."

Of course, I landed many a huge design project. And they honestly went just fine. But I also simply couldn't accept that I was "good enough" for my position. It all felt slightly fraudulent, as if I were "getting away" with something, which I now recognize as a surefire sign of Imposter Syndrome.

This term was first coined by psychologists Pauline Rode Clance and Suzanne Imes in 1978 to describe that crunchy and deeply uncomfortable experience of doubting your abilities and therefore your sense of belonging and ability to effectively contribute. During this, we become completely "other-oriented," consistently comparing and defining ourselves against others, and while it's common amongst all men and women, it unsurprisingly tends to show up more in minority groups.

The good news is that Imposter Syndrome follows a tried-and-true pattern, which when we slow it down looks something thing like this:

I remember that for me, my way of navigating through these complex waters was by leaning on other strengths I had, such as my ability to connect, pull groups together, and find humor, which recent MIT research recently coined as an "upside" of imposter thoughts (I call it coping and not addressing the root causes).

But the question persists: what can we do about it?

Whenever you feel like you might have Imposter Syndrome, please first check that you aren't in fact, just wading through a lot of societal garbage that's been heaped on top of you (read: you're a minority, woman, etc.). The system, in that case, may be working exactly as designed if you are feeling this way to keep you exactly where you are. (Or, as I like to say, the table wasn't built for you to sit at it, which means it may be time to build your own table).

Second, I'd like to suggest that Imposter syndrome isn’t a syndrome at all—it’s a pattern of self-doubt designed to keep you emotionally safe from specific risks. These risks are oftentimes things like being seen as a fraud (rejection), failing publicly (humiliation), and disappointing others (shame).

The work here is understanding and healing the root causes of your relationship to these risks, which are personal and unique to you and your history. One way to do this is by setting up some easy experiments for yourself to see what else may be true as you confront these risks. You can do things such as:

Speak up in a meeting as if your perspective has value.

Share what you are passionate about in your business or whatever your current project is as if it really matters.

Note the outcome and how it felt in your body.

So, if you’re feeling like an imposter these days, know this: you’re not alone. You’re not broken. And you’re definitely not disqualified from belonging or contributing. You’re likely just at the edge of something new—and that’s where all real change begins.

Keep going. Keep experimenting. And remember: the goal isn’t to eliminate doubt entirely. It’s to move forward with more of you in the driver’s seat.

If this resonated with you, I’d love to hear—what’s one “experiment” you might try this week to challenge your own imposter thoughts? Feel free to share below in the commens or just take a quiet moment to name it for yourself.

That counts, too.